22 January 2008 It is always interesting to learn how we are perceived by others. I have this opportunity at times provided by Sitemeter, which allows me to study how visitors travel to and from my site.A very interesting series of visits occurred through a link to my site on the "AppleInsider" Forum. The topic of discussion follows below:

It is always interesting to learn how we are perceived by others. I have this opportunity at times provided by Sitemeter, which allows me to study how visitors travel to and from my site.A very interesting series of visits occurred through a link to my site on the "AppleInsider" Forum. The topic of discussion follows below:

"It looks to be kind of a dangerous time to invest - if you invest in the US what if the dollar keeps on dropping? If you invest overseas what if the dollar rebounds? What about recession, inflation, rising interest rates, bad loans and problems borrowing money as a result (even for good companies)?

"I am looking at commercial REITs - they seem low now, provide income, and have average returns greater than the stock market. The only stocks that look like good buys right now are Cisco and Starbucks.

"What are you investing in/thinking of investing in?"

One participant chose to cite my most-commonly-visited article on the $5000 inflation-adjusted long-term gold price target. Citing my article, the person commented as follows: "Gold!

"

http://laurencehunt.blogspot.com/2007/07/golds-1980-high-think-5000-per-ounce.html "Quote:

| 'The implication of this recalculation is that by normal cyclical fluctuation alone, it is reasonable to expect the current gold bull market to top out somewhere higher than $5000 per ounce.' |

"Now, there are a lot of reasons why this won't happen...

"One being that it starts becoming child's play to mine it our of the oceans once it gets above $1,200/ounce. Which was a similar problem back in the 80s which is why it never broke $900. Well, that and a few other issues."

As I am not a participant at this site, I was not able to reply directly, and believe me, there is much I could have said.Fundamentally, however, the most pleasing aspect of reading over this discussion was the confirmation of broad scepticism pervading the investment community with respect to the wisdom of investing in gold (despite gold's being essentially the present decade's best-performing investment sector so far - apart perhaps from energy and several other of gold's cousins and extended family members).Also of interest was the contributor's primary argument, that when gold becomes sufficiently valuable, much more will be produced, perhaps we'll even begin to filter it out of the oceans!I cannot comment on ocean filtration recovery of gold. I am not an expert. It is a "for real" technology, as I discovered with the help of Google, which yielded the following link on Science Direct, a reputable professional scientific site.

New Scientist has considered the matter of gold in sea water, and cautions us that no one will grow wealthy by extracting one gram of gold per 100 million tons of sea water: "The presence of gold in sea water has been known since 1872 and has, since that time, motivated much hope of financial gain. But as analytical techniques have improved, the estimates of the amounts in the oceans have decreased dramatically. These most recent estimates are three orders of magnitude lower than those made before 1988. There may indeed be gold in the oceans, but not enough to make anyone rich."

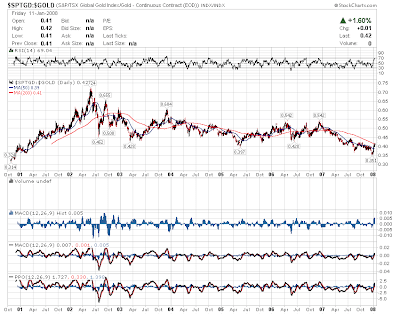

However, one matter of which I am quite confident is that the folks at Barrick and Newmont have devoted some thought to how much gold can be recovered over the next several years, by what means, and at what prices. The bottom line is that there is no system for producing gold, no how matter cost-effective, which does not involve extensive lead times, and only a very gradual increase in our total store of global gold supplies.In short, all of the mined gold in the world - approximately 140,000 tons above ground (with an additional known or inferred 50,000 tons underground, half of which is in South Africa) - will soon fill an elongated cube or block the base of which is the size of a single tennis court. Gold mining adds about 2% per year to the total mined supply. It takes ten years and often much longer to commission and bring a new gold mine into operation (assuming the mine is not confiscated by greedy governments, etc.) At today's present production rate of less than 4,000 tons per year, we will still require 20 more years to complete our first-ever tennis-court-sized block of gold. Today's above-ground gold is presently valued at approximately $4 trillion US dollars, about double its value of only 4 years ago, and more than triple its value in 2001. No matter what you do, you will not be able to increase the world's minuscule supply of gold by a very great amount. What you must reckon with, primarily, is the potential of increased demand for gold as the following asset classes decline in value: currencies, equities, bonds, real estate, manufacturing capacity and manufactured goods.That is, the real issue potentially driving the value of gold is not the prospect of minimally or greatly increased supplies of gold, as the author at the AppleInsider Forum suggests, but of greatly increased demand for gold as alternative asset classes fail as viable investments.We presently live in a world in which gold and precious metals taken as a whole represent far less than one percent of the value of all capital assets. For example, all of the gold stocks constituting the Amex Gold Bugs Index, at about $160 billion in market capitalization, represent approximately 0.3 to 0.4% of the market value of all the companies in the world, estimated by Wikipedia at about $51 trillion US dollars as of March 2007, and less than the market capitalization of Google ($182 billion today), even following one of the steepest slides in US stock valuations in many years.So long as people are not buying gold because it might cheaply be separated from ocean water at some future point in time, one can rest assured that all of those who might one day desire to own gold are not presently contemplating doing so.In short, every indicator I can see presages a gold price much higher than today's value.

The bottom line is that there is no system for producing gold, no how matter cost-effective, which does not involve extensive lead times, and only a very gradual increase in our total store of global gold supplies.In short, all of the mined gold in the world - approximately 140,000 tons above ground (with an additional known or inferred 50,000 tons underground, half of which is in South Africa) - will soon fill an elongated cube or block the base of which is the size of a single tennis court. Gold mining adds about 2% per year to the total mined supply. It takes ten years and often much longer to commission and bring a new gold mine into operation (assuming the mine is not confiscated by greedy governments, etc.) At today's present production rate of less than 4,000 tons per year, we will still require 20 more years to complete our first-ever tennis-court-sized block of gold. Today's above-ground gold is presently valued at approximately $4 trillion US dollars, about double its value of only 4 years ago, and more than triple its value in 2001. No matter what you do, you will not be able to increase the world's minuscule supply of gold by a very great amount. What you must reckon with, primarily, is the potential of increased demand for gold as the following asset classes decline in value: currencies, equities, bonds, real estate, manufacturing capacity and manufactured goods.That is, the real issue potentially driving the value of gold is not the prospect of minimally or greatly increased supplies of gold, as the author at the AppleInsider Forum suggests, but of greatly increased demand for gold as alternative asset classes fail as viable investments.We presently live in a world in which gold and precious metals taken as a whole represent far less than one percent of the value of all capital assets. For example, all of the gold stocks constituting the Amex Gold Bugs Index, at about $160 billion in market capitalization, represent approximately 0.3 to 0.4% of the market value of all the companies in the world, estimated by Wikipedia at about $51 trillion US dollars as of March 2007, and less than the market capitalization of Google ($182 billion today), even following one of the steepest slides in US stock valuations in many years.So long as people are not buying gold because it might cheaply be separated from ocean water at some future point in time, one can rest assured that all of those who might one day desire to own gold are not presently contemplating doing so.In short, every indicator I can see presages a gold price much higher than today's value. $5000 gold is many years away, of this there can be no doubt. But $1000 gold does not appear to be a distant vision at all - particularly following the US Federal Reserve's most recent currency devaluation - attributable to today's dramatic 0.75% cut in its federal funds lending rate.Continued rate cuts assure ongoing devaluation of all "paper" currencies, and sustained reinforcement of the market value of gold and of gold mining shares.Take my advice. The prospect of scientists producing gold from seawater will not erode the value of your long-term investment in gold. Have much more fear of central bankers and government leaders continually undermining the value of your local currency - whatever it might happen to be!

$5000 gold is many years away, of this there can be no doubt. But $1000 gold does not appear to be a distant vision at all - particularly following the US Federal Reserve's most recent currency devaluation - attributable to today's dramatic 0.75% cut in its federal funds lending rate.Continued rate cuts assure ongoing devaluation of all "paper" currencies, and sustained reinforcement of the market value of gold and of gold mining shares.Take my advice. The prospect of scientists producing gold from seawater will not erode the value of your long-term investment in gold. Have much more fear of central bankers and government leaders continually undermining the value of your local currency - whatever it might happen to be!

I am shocked to learn that these conferences are still taking place, with the next one coming to Toronto on March 29-30, 2008. The usual suspects will be present - including the kingpins of the long-deflated real estate bubble and other new age icons - Donald Trump, Anthony Robbins, George Foreman, David Bach, the Teachers from "The Secret," and an additional "all-star line-up," including Jack Canfield, Alan Greenspan(!?!), and Magic Johnson.

I am shocked to learn that these conferences are still taking place, with the next one coming to Toronto on March 29-30, 2008. The usual suspects will be present - including the kingpins of the long-deflated real estate bubble and other new age icons - Donald Trump, Anthony Robbins, George Foreman, David Bach, the Teachers from "The Secret," and an additional "all-star line-up," including Jack Canfield, Alan Greenspan(!?!), and Magic Johnson. Trump and Robbins may still be running real estate wealth conferences (Kiyosaki pulled out of that game in 2005), but the bus stop benches are now telling a different story.

Trump and Robbins may still be running real estate wealth conferences (Kiyosaki pulled out of that game in 2005), but the bus stop benches are now telling a different story. I would caution against following the pied piper on this particular adventure.

I would caution against following the pied piper on this particular adventure.